The last tidepool of 2025 was sandwiched between my daughter’s piano lesson and sunset. I arrived at False Point, bordering La Jolla and Pacific Beach, at 3:30 p.m., leaving myself about an hour to explore.

I was joined on this tidepool adventure by three friends. Our methodology was simple: move slowly toward the setting sun, taking turns carefully flipping a rock at each pool. Along the way, fellow observers helped spot a California two-spotted octopus in no hurry to conceal herself, a wiggly California sea hare, and an array of bat stars neatly arranged along the contours of a mossy rock. At one point, many tidepool-goers paused their search to admire the skill of a great egret. Probing with her stylish yellow foot, she bagged two or three tidepool fish (perhaps a sculpin or baby opaleye) in less than a minute.

Often nestled between rocks were wavy turban snails of all sizes. One rock Sussi picked up revealed firmly attached chitons of monstrous proportions—aptly named conspicuous chitons. Most flipped stones exposed brittle stars in the act of sneaking away. Many were banded brittle stars, marked by alternating gray and brown bands. I found one without bands, with all five limbs of different lengths and a tiny claw at each tip. It matched an Esmark’s brittle star, known for its extremely detachable arms—especially brittle even among this family. Because of their fragility and sensitivity to environmental stress, their presence in tidepools is considered a sign of a healthy local marine ecosystem.

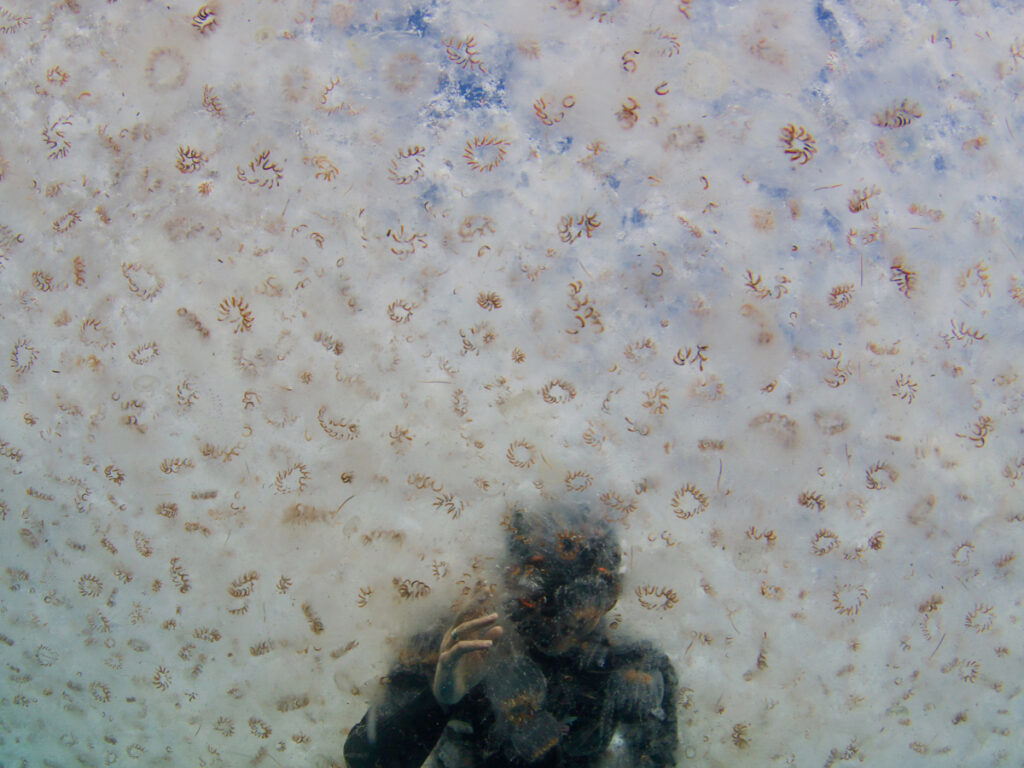

Under nearly every flipped rock were purple sea urchins. Their many spines offer protection and trap tiny—and sometimes not-so-tiny—rocks. Those spines also gave us pause before we picked them up. They sat still at first, then began to move in search of a new hiding place. Having our hands walked across by countless little spiny “feet” produced a funny feeling: mildly ticklish and slightly sticky. That sensation came from the suction-cup-tipped tube feet as the urchins moved while simultaneously shuttling food toward their central mouthpart, known as “Aristotle’s Lantern”.

Although we didn’t need to worry about being consumed by these small herbivores, our broader interests are closely tied to them. The juvenile sea urchins we held in our palms had green spines—a youthful look they sport before turning a vivid purple as adults. Purple sea urchins feed on the holdfasts of giant kelp and can devastate kelp forests, which are vital to coastal ecosystems. After a photo or two, we returned those little spiny balls to their rocky homes. But was that the right thing to do? According to a KQED article, perhaps we should have thrown a sea urchin party to help save the kelp forests we love to explore on our ocean swims.

Or maybe we’ll save that for our next tidepool visit.

The list of species found on this visit:

- Purple sea urchin ((Strongylocentrotus purpuratus).

- Wavy Turban snail (Megastraea undosa).

- Brittle Star (class Ophiuroidea):

- Banded Brittle star (Ophionereis annulata)

- Esmark’s brittle star (Ophioplocus esmarki)

- Conspicuous chiton (Stenoplax conspicua)

- Bat star (Patiria miniata)

- California two-spotted octopus (Octopus bimaculoides)

- California sea hare (Aplysia californica)