I have a sneaking suspicion that my backyard chickens know more about botany than I do; they recently proved me right!

On my weekly visit to the Farmers Market, I amble along the Rattlesnake Creek—a trail that separates residential homes from horse ranches. The ample spring rains this year brought an eruption of green growth to the riparian habitat along the trail.

Besides fresh seasonal produce for my kitchen, I usually ask the farmers for carrot leaves—the part of the carrot that customers generally discard—to bring to my hens, who eagerly devour those fresh greens as feasts.

Late spring, weeds had taken over half of the Rattlesnake Creek trail; meanwhile, carrot tops were disappearing at the Farmers Market: the carrots were in a low season.

Not wanting to disappoint my hens and brainstorming ideas along the trail, I noticed some plants with leaves resembling those of the carrots. Perhaps chickens would like them too, I thought, pulled a handful of the tender green leaves, and snapped a photo of the plant.

Once home, I presented the treat. The hens, however, “welcome” my present with only cold stares. I was mystified and decided to find out more about this plant. I fed the photo to PictureThis app; the result shocked me: poison hemlock!

Did I almost feed my chickens a poison that killed the famous philosopher?! My ensuing investigations confirm the identity of these plants.

How to Identify Poison Hemlock?

When searching for plants that resemble carrots, it’s not uncommon to mistake poison hemlock, Conium maculatum[1], for the real thing since they both belong to the carrot family, Apiaceae, which also includes common domesticated plants, such as carrot, parsley, celery, and fennel. However, spotting poison hemlock unequivocally to avoid its toxin is not difficult once you learn its distinctive characters.

Close comparison of domesticated carrots, Daucus carota subsp. sativus, and poison hemlock shows that the feathery, clearly divided leaves of carrot are different from the broader, triangular leaves of poison hemlock. The distinction, however, is less obvious when poison hemlock leaves are young (see featured image).

Another way to distinguish poison hemlock is to examine the stems. Poison hemlock stems are smooth, hairless, and hollow, with purplish red spots, while wild carrot stems are hairy without spots. The species name, maculatum, means “spotted” in reference to this feature. The spots are visible on young and mature plants of the second year of this biennial, but they may NOT be discernible on the first-year plants.

A robust plant, especially growing in its favorite wet habitat (such as the riparian habitat of Rattlesnake Creek), poison hemlock can grow over six feet. By June, those tender, carrot-like plants of early spring have reached beyond eight feet and are embellished with cream-color, umbrella-like flowers. By now, another trait of hemlock is no longer subtle—the plant radiates the unpleasant smell of mouse urine from yards away.

Toxic Effects of Poison Hemlock

The killer of Socrates carries deadly alkaloids: coniine and γ-coniceine [2], which target the nervous system, particularly the neuromuscular junctions that control muscle movement.

The effects of these toxins are spelled out in its Latin name; “Conium,” comes from the Greek word “konas”—“to whirl about”—describing the dizzying effects of the plant’s poison after ingestion.

The symptoms [3] of poisoning by poison hemlock include confusion, dizziness, trembling, muscle weakness; in severe cases, hemlock poisoning can lead to respiratory failure, even death. All parts of the poison hemlock are highly toxic. Ingesting even small amounts of the plant can be dangerous. Different species have different reactions to coniine. In humans, 3 mg of coniine produces symptoms. Up to 150–300 mg coniine can be tolerated, which translates to 6–8 leaves (6 g) [2].

Despite of its high toxicity, poison hemlock had been used historically as a medicine to treat a variety of illnesses, including indolent tumor and epilepsy. The practice eventually stopped. The last official record of medical use of poison hemlock was in 1938 in the British Pharmaceutical Codex. It was due to the difficulty in manufacturing and administering the optimal quantity and risk of overdosing.

Are Poison Hemlocks Found Around You?

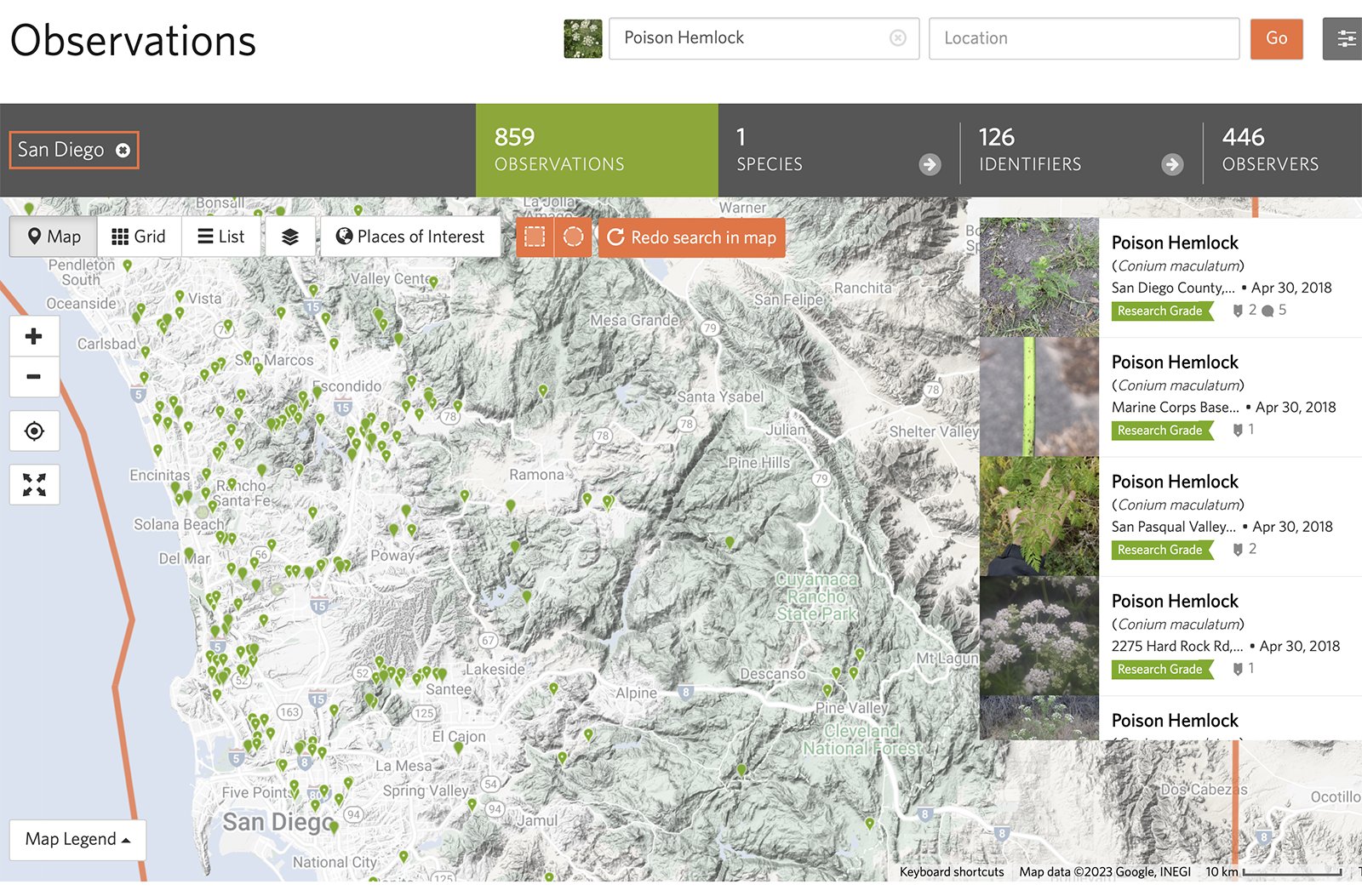

Introduced as an ornamental plant in the 1800s from Europe, poison hemlock spreads across most of North America. It favors damp soil, particularly near streams, like Rattlesnake Creek. It also takes residence on roadsides, edges of cultivated fields, and waste areas. Once I learned the features of poison hemlock, I started to notice its presence throughout San Diego.

On iNaturalist, over 800 observations of poison hemlock have been recorded in San Diego County [4]. According to San Diego County Native Plants [5], the only other Apiaceae family plants with some resemblance to poison hemlock and similarly widely observed in San Diego are American wild carrot (interestingly, also called Rattlesnake weed), Daucus pusillus (almost 700 observations), and Common celery, Apium graveolens (close to 600 observations). American wild carrots are diminutive, and common celery both look and smell like celery; both can be easily distinguished from poison hemlock. So, if you live in San Diego, you can be pretty certain that a wild plant fitting the forementioned features is poison hemlock and should be avoided.

Reported hemlock poisoning are generally attributed to accidental consumption [6]. Springtime is a prime time for foraging, which can be an exciting activity. However, doing so without proper knowledge and familiarity of your local plant community can be fatal. Learning key features and distributions of commonly found toxic plants helps us to avoid potentially harmful encounters and appreciate the natural world around us with greater awareness.

If you are unsure about a particular plant’s identity, use a plant identification guide or consult with a qualified botanist to ensure your safety.

Unless—you just want to rely on the wit of your chickens.

References:

- Wikipedia Contributors. “Conium Maculatum.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 July 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conium_maculatum.

- Hotti, Hannu, and Heiko Rischer. “The Killer of Socrates: Coniine and Related Alkaloids in the Plant Kingdom.” Molecules, vol. 22, no. 11, 14 Nov. 2017, p. 1962, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111962.

- “Hemlock Poisoning: Symptoms, Treatment & Prevention.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24122-poison-hemlock.

- “Poison Hemlock (Conium Maculatum).” INaturalist, www.inaturalist.org/taxa/52998-Conium-maculatum. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

- Lightner, James. San Diego County Native Plants. San Diego, Calif., San Diego Flora, 2011.

- Rizzi, D., et al. “Clinical Spectrum of Accidental Hemlock Poisoning: Neurotoxic Manifestations, Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Tubular Necrosis.” Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, vol. 6, no. 12, 1 Jan. 1991, pp. 939–943, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/6.12.939. Accessed 2 Dec. 2020.

* Last update on August 3, 2023.