At the beginning of 2025, I took a ten-week Wilderness Basic Course (WBC) offered by the San Diego Sierra Club. The course taught basic backpacking and wilderness navigation skills, as well as some more advanced techniques for a trip to camp in the snow. The course carried me far beyond technical skills. Each trip opened a small window onto a larger world, offering fleeting glimpses of a vastness of place and time that stretched well beyond the boundary of my daily routine.

By chance and by choice, I found myself drawn to one of the largest protected desert landscapes in the West—Anza Borrego Desert State Park—nearly 650,000 acres and just an hour’s drive from the sprawl of San Diego. Over three visits, I sampled the vast park from north to south. I climbed toward Villager Peak in the Santa Rosa Mountains, looking down the flat desert floor of Clark Valley to the west and Salton Sea gleaming to the east. I wandered among the caves and mud hills of the Coyote Mountains, where the wind ran its invisible hands through the rock and the earth had been shaped by forces both sudden and slow. Finally, at Whale Peak, in the heart of it all, I watched Granite Mountain stand guard to the west, halting the clouds and stealing the rain before they could reach the desert.

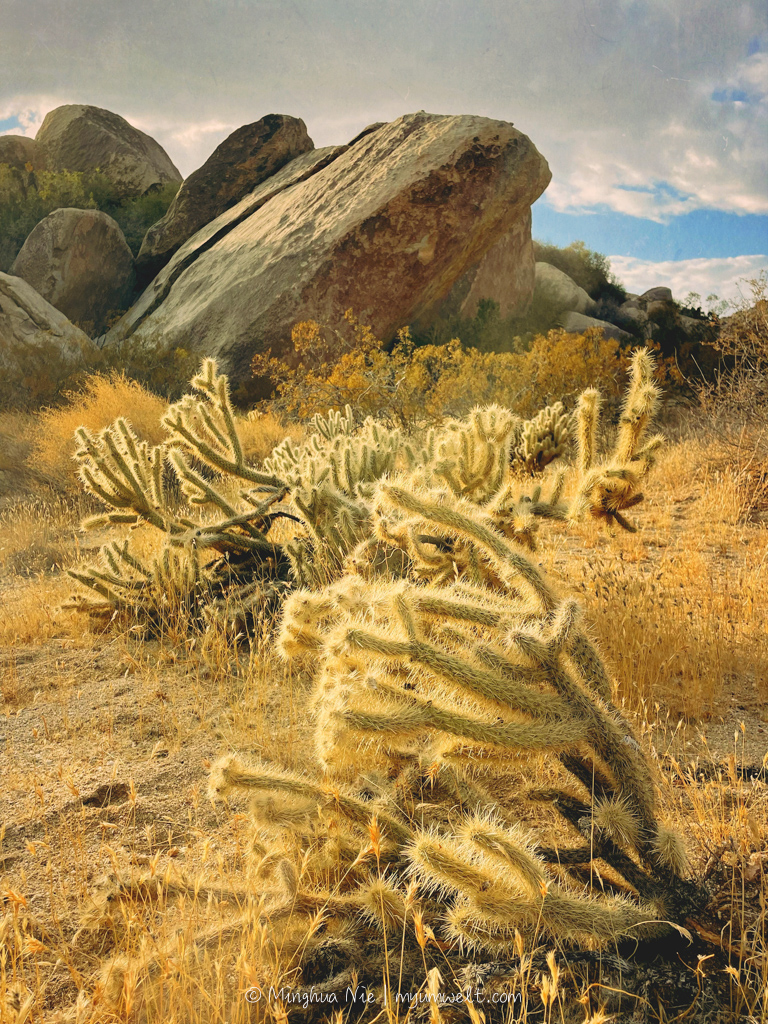

The desert, in its immensity, defies grasping and needs no explanation. We carried more water than we did food, our packs heavy with necessity, a reminder of the land’s indifference to human frailty. Yet, even in its seeming barrenness, the desert teemed with life and bore the marks of an ever-changing past. The dry rivers of slot canyons were penetrated by the burst of liveliness of the heartleaf suncups. The highland desert bristled with bandits of chollas, waiting to ambush passing hikers. Along some trails, the arid air was perfumed with the scent of desert lavender. And beneath our feet, layers of history were written into the land itself—fossils of giant sand dollars and snails, hills piled high from ancient shells, boulders and rocky mounts hollowed by wind, and canyons twisted and tunneled by water over millennia.

And finally, Mammoth Mountain—snowbound, luminous, a final passage in this story of wilderness. As I stood among the drifts, I felt again what the desert had taught me: that the world is old, vast beyond imagining, and yet, in that moment, it belonged to me.